How Greece entered the Euro

The audience of the film is again in Greece. They see how people incredulously look at German headlines: "Why do we have to bail out the lazy Greeks?" "Greece - their own  fault". The country had already cheated with its entry to the Euro and was unwilling to reform.

fault". The country had already cheated with its entry to the Euro and was unwilling to reform.

The film then shows the real story: In 1999, Greece was first not allowed to attain EU membership. Public debt was too high. To overcome this obstacle, a certain Lucas Papademos, CEO of the Greek Central Bank, organised a "tour de force". The banks Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and United Bank of Switzerland (UBS) offered additional billions of loans to the state that did not appear in the state budget: Future profits from motorway tolls and airport taxes and the state lottery were "traded away" for these loans. With the help of the Goldman Sachs department that was headed by today's ECB boss Mario Draghi, additional debts of the public budget were transferred as long-term loans to the Greek Central Bank via the London letterbox company Titlos. In this way, Papademos managed to magically reduce the Greek public debt . And so the country was able to join the Eurozone with a big round of applause from the banks. Of course this was cheating. But the "swindler" Papademos then became the ECB's vice-president. Everyone always knew about the real level of Greek public debt. The EU statistics authority Eurostat had already made a detailed list in 2003 of the applied tricks inspired by Goldman Sachs. This was now also confirmed by Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the Euro Group: They only wanted to leave Germany's and France's good business in Greece undisturbed.

From a "Swindler" to a Prime Minister

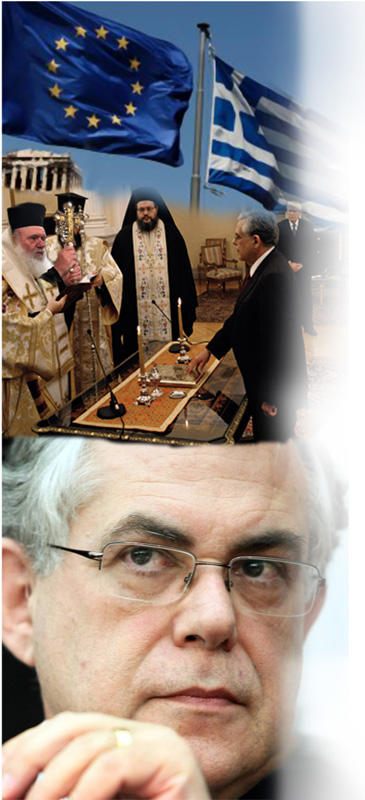

The events so far were astonishing enough. However, twenty years later, the same "swindler" Papademos turns up again, now as Prime Minister and saviour of Greece. At the beginning of 2011, the country was already in a disparate situation: the preconditions of the first bailout package had left scars: food sales had dropped by 39%, investment by 50%. Pharmacies only provided medicine for cash. Prescriptions were no longer accepted because the health insurances could no longer pay. The hospitals were on the brink of collapse. Then President Papandreou announced a referendum on the "second rescue package". For the Troika of European Union (EU), European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), however, the risk was too high. Papandreou was urged to resign and replaced by Lucas Papademos. He was presented as a "technocrat" and took the oath of office outside the parliament, in absence of Members of Parliament, with his right hand on the bible. The orthodox archbishop Ieronymos of Athens, whose church does not pay any taxes, sang the Kyrie Eleison (Lord, have mercy).

Mister Papademos now had another difficult task: The Greek public debt was still the risk of international financial corporations. But the "markets" were already betting on Greece's bankruptcy. So the banks don't like sitting on their treasure of highly profitable Greek debt (interest rates of more than 6%). They could become worthless in a meltdown. Mister Papademos calmed down the banks. As he left office, the risk of the Greek debt no longer was in the hands of the banks. It is now our risk. The more than 240 billion euro in debt were transferred to Europe's taxpayers. Were we ever asked whether we want them? Every hour, this amount increases by 10 billion euro. The billions of the "rescue packages" for Greece have made rich Greek richer and prevented losses for hedge funds and banks. The billions of "aid" were made private wealth. And the country was economically driven to the abyss. The bailout brought hunger and unemployment to every second young person. Now the Greeks are allowed to vote gain. They can also leave the Eurozone, too.

Good bank instead of bad bank

In this sense, it is absurd to save all banks with EUR19 billion. According to the Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz and Willem Buiter as well as major economic players such as George Soros, the state should lead the "systemically relevant" banks towards an orderly insolvency. The state should only buy the "good bonds" that are connected to the real economy and savings deposits. With these bonds and the network of branch offices, the state could found "good banks". For employees and clients of the previous bank, only the name and the management would change initially. According to Stiglitz and Soros, the "good bank" could seamlessly assume the core tasks of the banking system. Old banks, on the other hand, would continue to sit on the toxic investment. The tab would then be picked up by, alongside the investors, precisely the speculators who are now being supported by the taxpayers.

In this sense, it is absurd to save all banks with EUR19 billion. According to the Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz and Willem Buiter as well as major economic players such as George Soros, the state should lead the "systemically relevant" banks towards an orderly insolvency. The state should only buy the "good bonds" that are connected to the real economy and savings deposits. With these bonds and the network of branch offices, the state could found "good banks". For employees and clients of the previous bank, only the name and the management would change initially. According to Stiglitz and Soros, the "good bank" could seamlessly assume the core tasks of the banking system. Old banks, on the other hand, would continue to sit on the toxic investment. The tab would then be picked up by, alongside the investors, precisely the speculators who are now being supported by the taxpayers.

Regulation is indispensible and possible

At the end, the film shows that these alternatives are not only seriously calculated: they have also been implemented with success. Leading up to 1933, the apparently indomitable power of financial capital had already existed for some 100 years with crisis every seven years or so. This appeared to be natural law. Yet shortly after the global economic crisis in 1939, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to impose fundamental regulations on the financial markets. The Glass Steagal Act forced financial institutes to decide: either they are a strongly regulated business bank, concentrating on the security of deposits and credits to the real economy; or they opted for the securities business, in which they could only resort to the assets of the shareholder. Trade with derivatives was banned. Later, no bank was allowed to take over a competing bank from another US federal state. It was no longer allowed for any financial institute to become systemically relevant. Wall Street cried and predicted catastrophe. But the Act held out for over 60 years and provided for the USA - for the world - many decades of relatively stable economic relations.